Understanding Modules, Import and Export in JavaScript

In the early days of the Web, websites consisted primarily of HTML and CSS. If any JavaScript loaded into a page at all, it was usually in the form of small snippets that provided effects and interactivity. As a result, JavaScript programs were often written entirely in one file and loaded into a script tag. A developer could break the JavaScript up into multiple files, but all variables and functions would still be added to the global scope.

But as websites have evolved with the advent of frameworks like Angular, React, and Vue, and with companies creating advanced web applications instead of desktop applications, JavaScript now plays a major role in the browser. As a result, there is a much greater need to use third-party code for common tasks, to break up code into modular files, and to avoid polluting the global namespace.

The ECMAScript 2015 specification introduced modules to the JavaScript language, which allowed for the use of import and export statements. In this tutorial, you will learn what a JavaScript module is and how to use import and export to organize your code.

Modular Programming

Before the concept of modules appeared in JavaScript, when a developer wanted to organize their code into segments, they would create multiple files and link to them as separate scripts. To demonstrate this, create an example index.html file and two JavaScript files, functions.js and script.js.

The index.html file will display the sum, difference, product, and quotient of two numbers, and link to the two JavaScript files in script tags. Open index.html in a text editor and add the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>JavaScript Modules</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Answers</h1>

<h2><strong id="x"></strong> and <strong id="y"></strong></h2>

<h3>Addition</h3>

<p id="addition"></p>

<h3>Subtraction</h3>

<p id="subtraction"></p>

<h3>Multiplication</h3>

<p id="multiplication"></p>

<h3>Division</h3>

<p id="division"></p>

<script src="functions.js"></script>

<script src="script.js"></script>

</body>

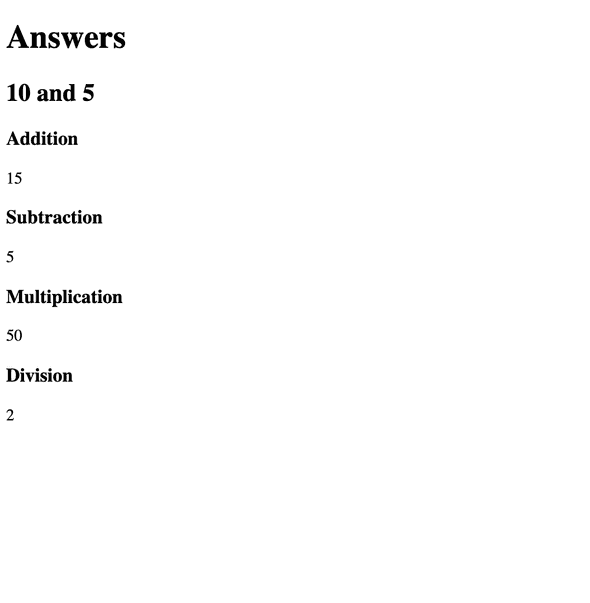

</html>This HTML will display the value of variables x and y in an h2 header, and the value of operations on those variables in the following p elements. The id attributes of the elements are set for DOM manipulation, which will happen in the script.js file; this file will also set the values of x and y. For more information on HTML, check out our How To Build a Website with HTML series.

The functions.js file will contain the mathematical functions that will be used in the second script. Open the functions.js file and add the following:

function sum(x, y) {

return x + y

}

function difference(x, y) {

return x - y

}

function product(x, y) {

return x * y

}

function quotient(x, y) {

return x / y

}Finally, the script.js file will determine the values of x and y, apply the functions to them, and display the result:

const x = 10

const y = 5

document.getElementById('x').textContent = x

document.getElementById('y').textContent = y

document.getElementById('addition').textContent = sum(x, y)

document.getElementById('subtraction').textContent = difference(x, y)

document.getElementById('multiplication').textContent = product(x, y)

document.getElementById('division').textContent = quotient(x, y)After setting up these files and saving them, you can open index.html in a browser to display your website with all the results:

For websites with a few small scripts, this is an effective way to divide the code. However, there are some issues associated with this approach, including:

- Polluting the global namespace: All the variables you created in your scripts—

sum,difference, etc.—now exist on thewindowobject. If you attempted to use another variable calledsumin another file, it would become difficult to know which value would be used at any point in the scripts, since they would all be using the samewindow.sumvariable. The only way a variable could be private was by putting it within a function scope. There could even be a conflict between anidin the DOM namedxandvar x. - Dependency management: Scripts would have to be loaded in order from top to bottom to ensure the correct variables were available. Saving the scripts as different files gives the illusion of separation, but it is essentially the same as having a single inline

<script>in the browser page.

Before ES6 added native modules to the JavaScript language, the community attempted to come up with several solutions. The first solutions were written in vanilla JavaScript, such as writing all code in objects or immediately invoked function expressions (IIFEs) and placing them on a single object in the global namespace. This was an improvement on the multiple script approach, but still had the same problems of putting at least one object in the global namespace, and did not make the problem of consistently sharing code between third parties any easier.

After that, a few module solutions emerged: CommonJS, a synchronous approach that was implemented in Node.js, Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD), which was an asynchronous approach, and Universal Module Definition (UMD), which was intended to be a universal approach that supported both previous styles.

The advent of these solutions made it easier for developers to share and reuse code in the form of packages, modules that can be distributed and shared, such as the ones found on npm. However, since there were many solutions and none were native to JavaScript, tools like Babel, Webpack, or Browserify had to be implemented to use modules in browsers.

Due to the many problems with the multiple file approach and the complexity of the solutions proposed, developers were interested in bringing the modular programming approach to the JavaScript language. Because of this, ECMAScript 2015 supports the use of JavaScript modules.

A module is a bundle of code that acts as an interface to provide functionality for other modules to use, as well as being able to rely on the functionality of other modules. A module exports to provide code and imports to use other code. Modules are useful because they allow developers to reuse code, they provide a stable, consistent interface that many developers can use, and they do not pollute the global namespace.

Modules (sometimes referred to as ECMAScript modules or ES Modules) are now available natively in JavaScript, and in the rest of this tutorial you will explore how to use and implement them in your code.

Native JavaScript Modules

Modules in JavaScript use the import and export keywords:

import: Used to read code exported from another module.export: Used to provide code to other modules.

To demonstrate how to use this, update your functions.js file to be a module and export the functions. You will add export in front of each function, which will make them available to any other module.

Add the following highlighted code to your file:

export function sum(x, y) {

return x + y

}

export function difference(x, y) {

return x - y

}

export function product(x, y) {

return x * y

}

export function quotient(x, y) {

return x / y

}Now, in script.js, you will use import to retrieve the code from the functions.js module at the top of the file.

Note:

importmust always be at the top of the file before any other code, and it is also necessary to include the relative path (./in this case).

Add the following highlighted code to script.js:

import { sum, difference, product, quotient } from './functions.js'

const x = 10

const y = 5

document.getElementById('x').textContent = x

document.getElementById('y').textContent = y

document.getElementById('addition').textContent = sum(x, y)

document.getElementById('subtraction').textContent = difference(x, y)

document.getElementById('multiplication').textContent = product(x, y)

document.getElementById('division').textContent = quotient(x, y)Notice that individual functions are imported by naming them in curly braces.

In order to ensure this code gets loaded as a module and not a regular script, add type="module" to the script tags in index.html. Any code that uses import or export must use this attribute:

<script type="module" src="functions.js"></script>

<script type="module" src="script.js"></script>At this point, you will be able to reload the page with the updates and the website will now use modules. Browser support is very high, but caniuse is available to check which browsers support it. Note that if you are viewing the file as a direct link to a local file, you will encounter this error:

Access to script at 'file:///Users/your_file_path/script.js' from origin 'null' has been blocked by CORS policy: Cross origin requests are only supported for protocol schemes: http, data, chrome, chrome-extension, chrome-untrusted, https.Because of the CORS policy, Modules must be used in a server environment, which you can set up locally with http-server or on the internet with a hosting provider.

Modules are different from regular scripts in a few ways:

- Modules do not add anything to the global (

window) scope. - Modules always are in strict mode.

- Loading the same module twice in the same file will have no effect, as modules are only executed once/

- Modules require a server environment.

Modules are still often used alongside bundlers like Webpack for increased browser support and additional features, but they are also available for use directly in browsers.

Next, you will explore some more ways in which the import and export syntax can be used.

Named Exports

As demonstrated earlier, using the export syntax will allow you to individually import values that have been exported by their name. Take for example this simplified version of functions.js:

export function sum() {}

export function difference() {}This would let you import sum and difference by name using curly braces:

import { sum, difference } from './functions.js'It is also possible to use an alias to rename the function. You might do this to avoid naming conflicts within the same module. In this example, sum will be renamed to add and difference will be renamed to subtract.

import { sum as add, difference as subtract } from './functions.js'

add(1, 2) // 3Calling add() here will yield the result of the sum() function.

Using the * syntax, you can import the contents of the entire module into one object. In this case, sum and difference will become methods on the mathFunctions object.

import * as mathFunctions from './functions.js'

mathFunctions.sum(1, 2) // 3

mathFunctions.difference(10, 3) // 7Primitive values, function expressions and definitions, asynchronous functions, classes, and instantiated classes can all be exported, as long as they have an identifier:

// Primitive values

export const number = 100

export const string = 'string'

export const undef = undefined

export const empty = null

export const obj = { name: 'Homer' }

export const array = ['Bart', 'Lisa', 'Maggie']

// Function expression

export const sum = (x, y) => x + y

// Function defintion

export function difference(x, y) {

return x - y

}

// Asynchronous function

export async function getBooks() {}

// Class

export class Book {

constructor(name, author) {

this.name = name

this.author = author

}

}

// Instantiated class

export const book = new Book('Lord of the Rings', 'J. R. R. Tolkein')All of these exports can be successfully imported. The other type of export that you will explore in the next section is known as a default export.

Default Exports

In the previous examples, you exported multiple named exports and imported them individually or as one object with each export as a method on the object. Modules can also contain a default export, using the default keyword. A default export will not be imported with curly brackets, but will be directly imported into a named identifier.

Take for example the following contents for the functions.js file:

export default function sum(x, y) {

return x + y

}In the script.js file, you could import the default function as sum with the following:

import sum from './functions.js'

sum(1, 2) // 3This can be dangerous, as there are no restrictions on what you can name a default export during the import. In this example, the default function is imported as difference although it is actually the sum function:

import difference from './functions.js'

difference(1, 2) // 3For this reason, it is often preferred to use named exports. Unlike named exports, default exports do not require an identifier—a primitive value by itself or anonymous function can be used as a default export. Following is an example of an object used as a default export:

export default {

name: 'Lord of the Rings',

author: 'J. R. R. Tolkein',

}You could import this as book with the following:

import book from './functions.js'Similarly, the following example demonstrates exporting an anonymous arrow function as the default export:

export default () => 'This function is anonymous'This could be imported with the following script.js:

import anonymousFunction from './functions.js'Named exports and default exports can be used alongside each other, as in this module that exports two named values and a default value:

export const length = 10

export const width = 5

export default function perimeter(x, y) {

return 2 * (x + y)

}You could import these variables and the default function with the following:

import calculatePerimeter, { length, width } from './functions.js'

calculatePerimeter(length, width) // 30Now the default value and named values are both available to the script.

Conclusion

Modular programming design practices allow you to separate code into individual components that can help make your code reusable and consistent, while also protecting the global namespace. A module interface can be implemented in native JavaScript with the import and export keywords. In this article, you learned about the history of modules in JavaSvript, how to separate JavaScript files into multiple top-level scripts, how to update those files using a modular approach, and the import and export syntax for named and default exports.

To learn more about modules in JavaScript, read Modules on the Mozilla Developer Network. If you'd like to explore modules in Node.js, try our How To Create a Node.js Module tutorial.

Comments